Building the new Hypermedia Systems

Clickbait title: Can you write a bestselling book in Typst?

A shiny new edition of Hypermedia Systems is out! Apart from incorporating typo and grammar fixes sent in by readers, the book was completely redesigned inside with a new layout. To achieve a much higher fidelity of design, we ported the book to Typst — the hot new LaTeX replacement.

Why change what works?

The first print release of HS was written in AsciiDoc. It seemed like a natural choice at the time – after all, many publishing houses trust AsciiDoc for their books. We learned the hard way that those publishers also have teams of engineers developing proprietary toolchains to produce their books. Vanilla AsciiDoc doesn’t actually have a way to produce good print output:

-

asciidoctor-pdfuses a rudimentary PDF generation library, and the output is just about readable, but not good – and you don’t have any good tools to change that. -

the venerable Pandoc can output AsciiDoc, but oddly can’t read it – so we can’t compile our book to LaTeX.

Your best option for producing a printable PDF, if you care at all about typesetting, is to compile to HTML, and print that to PDF. asciidoctor-web-pdf is a tool that wraps this workflow in a usable package, combined with Paged.js to polyfill the many features of CSS for print media that browsers don’t support. This is how we produced the first edition of HS, and it was a pain for multiple reasons.

-

Paged.js has bugs. One bug that was nasty to work around was one where using any CSS to modify the page numbers (say, resetting them after the front matter) would cause all the pages to revert to 0. I don’t know if this was fixed.

-

HTML with Paged.js is slow. The book has a little over 300 pages, and each page has a perceptible delay as it gets laid out. Even worse, I had to manually scroll the browser all the way to the bottom of the book before printing, or the back half of the book would be blank. Afterwards, printing would take what felt like a solid minute, though I never measured how long: Since presumably nobody at Firefox thought printing a page to PDF would be anything but instant, there’s no progress bar or any other indicator of success beyond the PDF appearing in the folder where it’s supposed to be.

-

The idiosyncrasies of this process meant that it only really worked on my machine, and I had to send PDFs back and forth with my co-authors and editor. The PDFs were absolutely massive and exceeded the Discord upload limit, so I uploaded each one to Google Drive.

-

Paged.js has more bugs – asides would refuse to break across pages while code blocks were all to eager to create widows and orphans – or disappear completely – which I had to work around in a whack-a-mole fashion. A few bugs seem to have made it into the final release.

-

AsciiDoc has facilities for indexing, but doesn’t support outputting them in HTML in any way. Worse, the mechanism I could have used to do it myself was deprecated and removed before the replacement was implemented. Our editor ended up creating an index by hand, which was appended to the PDF.

-

You go through all this effort only to be rewarded with very mediocre typesetting, since browsers use greedy algorithms for laying out text for performance reasons, yielding far worse line breaking compared to the dynamic programming algorithms of TeX.

Despite all this, we somehow produced a usable PDF. Most readers report being satisfied with the book’s design (Amazon’s failure to print a PDF consistently notwithstanding). The code that generated this PDF is not open source — initially, it was because we thought it might eat into print sales, but these days the real reason is that it might help someone else that tries to do this, and nobody should try to do this.

(If you have any “why didn’t you just” recommendations, feel free to post them in the comments on link aggregators — they might help someone else — but don’t send them directly to me. I assure you, I’ve evaluated all options available even if I didn’t mention them here.)

Speaking of link aggregators,

Typst

I first stumbled upon Typst when the author’s thesis was posted on the red site. Enthralled by its combination of quality typesetting, lightweight markup and an ergonomic scripting language tightly integrated, I knew that if I was ever part of another book project, I would use Typst.

I rewrote my CV in it, as well as some documentation for an old project. This only confirmed my initial impression — Typst is a joy to use, and the scripting language is so good I wish it was a programming language in its own right.

But I couldn’t use Typst for Hypermedia Systems, because Typst didn’t support HTML output. Imagine my excitement when a while ago, I realized Pandoc had added Typst support!

Porting the manuscript

As I mentioned before, Pandoc can’t read AsciiDoc. So how can I convert the 104537 words of HS into Typst? I was ready to do it by hand, but I decided to try something else first.

One of AsciiDoc’s primary output formats is DocBook XML. I don’t know what it is or who uses it, but Pandoc can read it! I converted the book to DocBook XML, and then to Typst. Except AsciiDoc was buggy and generated invalid XML, so I had to fix that first. And then massage the resulting Typst a bit more. And apply any future changes to the AsciiDoc source to the Typst version.

Still better than waiting for the PDF to render, though.

The code blocks

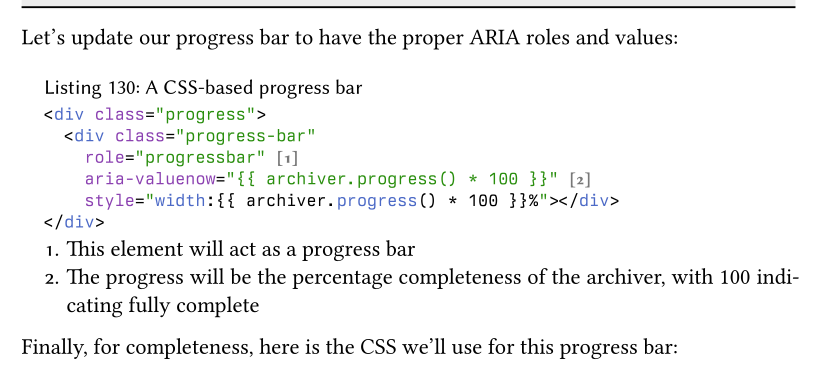

AsciiDoc has a unique style of code blocks where you can place markers in the code that refer to explanatory notes below the block – it looks like this:

[source,python]

----

print("Hello, world!") <1>

----

<1> The canonical first program in any language.

If you’ve read Hypermedia Systems, now you know how we made those. Typst doesn’t have any such feature, so with the great help of the Typst Discord community, I reimplemented it in about 50 lines of slightly cursed Typst code.

code-callouts.typ: a Hypermedia Systems literate experience

Before implementing code callouts, define a label, which we will use to mark code blocks we have already annotated. This is to prevent an infinite loop that occurs when we use this function in a show rule.

#let processed-label = <TypstCodeCallout-was-processed>

The function code-with-callouts takes a code block and a function to render callouts. A simple default implementation returns the annotation number in square brackets in grayed-out sans-serif font.

#let code-with-callouts(

it /*: content(raw) */,

callout-display: default-callout /*: (str) => content */

) /*: content */ = { ... }

Begin by checking if the code block has already been processed.

) /*: content */ = {

if it.at("label", default: none) == processed-label {

it

} else { ... }

}

The dance with it.at("label", default: none) is a way to access the code block’s label without throwing an error if it has none. If it doesn’t have this label, the real fun begins.

let (callouts, text: new-text) = parse-callouts(it.text)

parse-callouts is a function that extracts the callouts from the code block. We pass it the text of the code block – the plain, un-highlighted code as a string. It returns that text with the callout markers removed, and the callouts themselves in the form of an array of callout numbers for each line. This is in a way the meat of the whole operation, but it’s also pretty mundane string processing code, so I won’t dwell on it.

#let callout-pat = regex("<(\\d+)>(\\n|$)")

#let parse-callouts(

code-text /*: str */

) /*: (callouts: array(array(int)), text: str) */ = {

let callouts /*: array(array(int)) */ = ()

let new-text = ""

for text-line in code-text.split("\n") {

let match = text-line.match(callout-pat)

if match != none {

callouts.push((int(match.captures.at(0)),))

new-text += text-line.slice(0, match.start)

} else {

callouts.push(())

new-text += text-line

}

new-text += "\n"

}

(callouts: callouts, text: new-text)

}

Now that we have the callouts, we can render them. We do this by abusing show rules. A raw.line (object representing a line of raw text) knows its line number, so we can use that to look up the callouts for that line. We then iterate over the callouts and render them with the provided callout-display function.

show raw.line: it => {

it

let callouts-of-line = callouts.at(it.number - 1, default: ())

for callout in callouts-of-line {

callout-display(callout)

}

}

You might assume as I did that this would be the end of it and we could just return the code block, but there’s a catch. The code block still has the <1> markers in it, and we need to remove them. To do this, we create a new code block with the same attributes as the original, but with our new-text as the body. The fact that we create a brand new code block instead of returning the one we were given is what causes the infinite loop I mentioned earlier, so we apply the processed label.

let fields = it.fields()

let _ = fields.remove("text")

let _ = fields.remove("lines")

let _ = fields.remove("theme")

[#raw(..fields, new-text)#processed-label]

This is the code that powers the code blocks in the new edition of Hypermedia Systems. All you need to do is add a show raw.where(block: true): code-with-callouts to your Typst document, and you can have code blocks with callouts too!

The actual text of the callouts is just a list written below the code block. If I was implementing this from scratch, I might have had the code-with-callouts accept the content of the callouts as well and match them up to the code by text labels, but AsciiDoc uses numbers and makes you match them up manually, so I did too.

The index

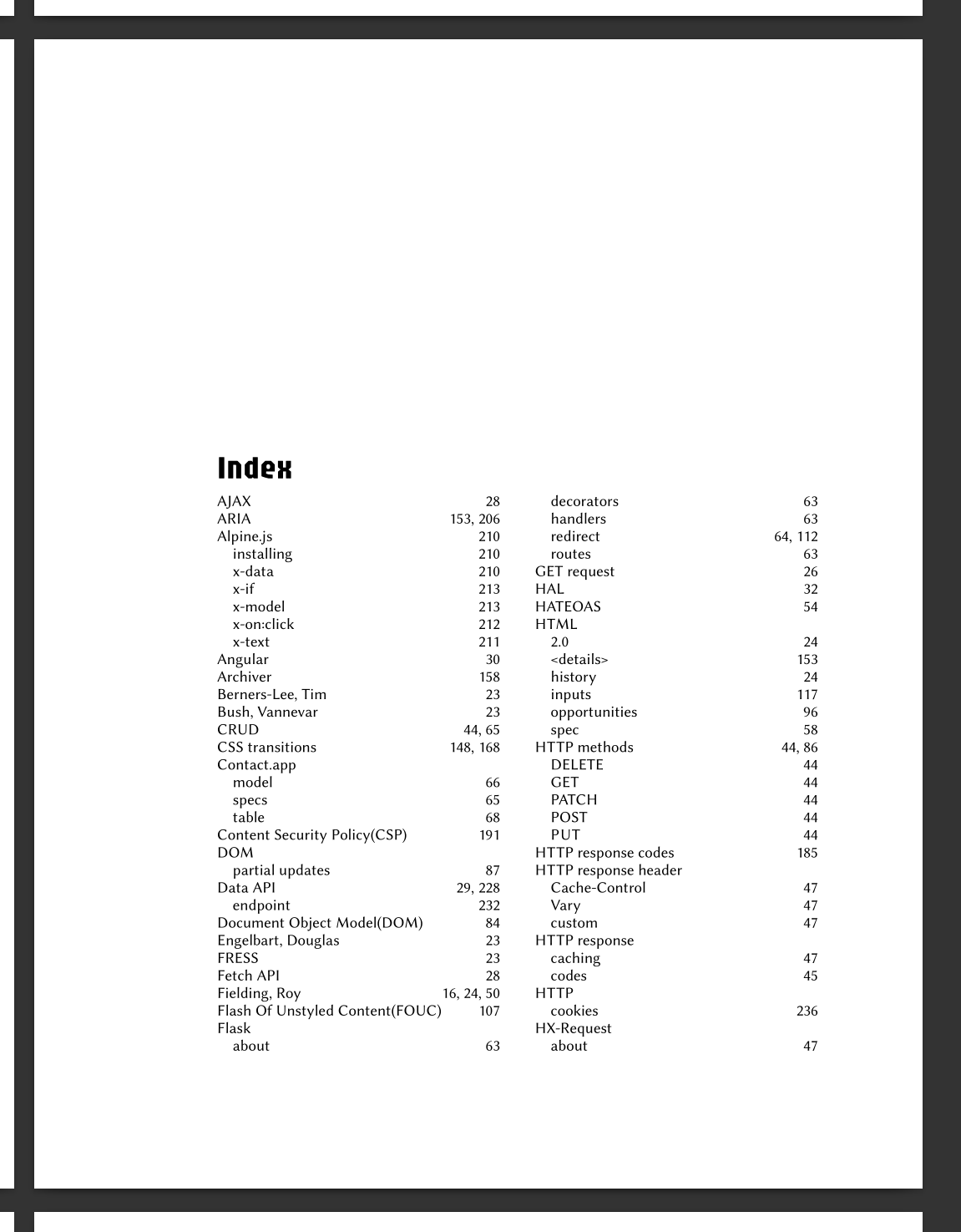

Typst has no indexing functionality by default, but its scripting and introspection capabilities are powerful enough to implement indexing at the library level. In fact, an indexing library already exists in the form of in-dexter, which is small enough that I made a modified version of it to have full control over the index’s appearance and to add support for hierarchical terms.

The print book

So far, I’ve talked about the most technically interesting parts of the migration and not the most important part: the actual product. Using a capable typesetting system instead of Print to PDF meant I could tweak almost every aspect of the book’s design, and the software would actually cooperate.

The new Hypermedia Systems uses indented paragraphs instead of block paragraphs. That is, the first line of a paragraph is indented, and there’s no space between paragraphs. What’s so special about that? You can definitely do that in HTML and CSS, right? Not if you want to do it well. Traditional style and my own preference dictate that indentations separate paragraphs, so the first paragraph after a non-paragraph element (like a heading or a list) should not be indented. This is a common typographic convention, but to do it in CSS is impossible in the general case without dozens, maybe hundreds of selectors to handle every special case. In Typst, you just give paragraphs a first-line-indent, and they know when to use it.

It’s a similar story with emphasis. The <em> element in HTML is italicized by default, and similarly for emph in Typst. When emphasis is used in an element that’s already italicized, the emphasis is shown by reversing the italics and making the emphasized text upright. With CSS, you might restyle <em> in all those contexts (and remember to revert it as needed). Container style queries might make this easier in CSS. In Typst, it’s the default behavior.

Other than styling features, Typst is also just better at typesetting, using line breaking algorithms similar to TeX. Especially compared to browsers with their greedy algorithms and weirdly small hyphenation dictionaries, Typst prose is a joy both to look at and to read.

I want HTML and CSS to be as capable in print as they are on screens. Unfortunately, browsers don’t seem as interested – the CSS Paged Media module remains largely unimplemented. While I would love a future where the same HTML code can back both online and print books (and PDF is relegated to an archival format), building separate web and print books from a Typst manuscript seems to be the best strategy for now.

The web book

Typst can produce a wonderful PDF for us, but we also need to publish the book online. While HTML output is a planned feature for the Typst compiler, no implementation currently exists. This is why I didn’t propose Typst while we were producing the first edition, before Pandoc gained support for reading and writing Typst.

The old hypermedia.systems was built with the static site generator Lume with an AsciiDoc plugin I wrote. For the new book, I wanted to test out [Müteferrika][], an online book publishing toolkit I’m building. The advantage of Müteferrika is that it understands the structure of a book (parts, chapters, frontmatter etc.). The disadvantage is that it was and still is an unfinished mess, so I had to fix a lot of bugs to get it to work for Hypermedia Systems.

The build process had to convert the Typst source to HTML, which I planned to do with Pandoc. Unfortunately, Pandoc doesn’t have full parity with the mainline Typst compiler, and spat out many errors when I first tried to convert the book. The fix for most of these was to replace direct property accesses with at calls and add null checks as needed.

Conclusion

The migration from AsciiDoc to Typst was a resounding success. I had to fudge a lot of tooling around book production, since Typst is still a young project and focused more on research papers than books, but the ecosystem is constantly growing and improving. Shiroa is a promising project for publishing web books with Typst, for example.

The web book is now live at hypermedia.systems. It has (as far as we could tell) everything the old web book had, and more. There’s a button at the bottom of each page where you can customize the colors of the website to your liking. For the print version, we’re switching from Amazon KDP to Lulu, which will hopefully result in more consistent printing.